Welcome to Chief Complaint! For those of you who are new, this newsletter features intermittent musings about medicine, gender, parenting, and body liberation — all from your friendly neighborhood primary care doc. I’m so happy you’re here.

I spend so much of my working life apologizing.

I know strong, ambitious women aren’t supposed to say they’re sorry. (Right? Isn’t there AI software that will comb through your emails and delete all the apologies?) But in my situation, I think it’s warranted.

Over and over again, twenty times a day, I apologize to my patients for running late.

Oh, how I hate being late all the time. It plagues my days as a primary care doctor. I feel terrible for making people wait, stuck in those uncomfortable, chilly little exam rooms with no natural light. It messes up their schedules, makes them late for work. They think they’ll be done at 2, and they end up leaving at 4. It makes me feel awful.

I hate it not just because I feel disrespectful of my patients, but it messes up my own schedule, too. My evenings are often unpredictable, and I’m never sure exactly when I’ll leave work. I’m often late to mid-day meetings. It makes me late to pick up my kid from daycare, late to classes I teach, late to lectures I have to give.

And I’m far from the only one. Everyone in health care is running late, all the time.

I remember when I was a medical student, I was once late to a meeting with a fellow, someone several rungs higher up on the ladder than I was. (I had misunderstood exactly when and where we were supposed to meet.) I offered to reschedule, and this (very kind) fellow told me no — “Let’s just get it done.” She ushered me into her office. “The longer you’re in medicine,” she said, “The more you realize everyone is always running late. You just get stuff done when you can.”

Mostly, my patients are gracious and say they understand. It’s not their first primary care rodeo.

But occasionally, they’re really pissed off. And understandably. There’s a power imbalance in asking someone to wait for me. It sends the message that my time is more valuable than theirs, and that I think I’m more important.

What is going on? Where does this culture of perpetual lateness come from? Who benefits from it?

Our appointments are scheduled for 20 minutes, back-to-back, with no buffer time between them. In a typical clinic day, I’ll see 20 - 30 patients.

I usually start off on time. But as the day goes on, a patient requires an extra five minutes here, an extra three minute there. Next thing I know, I’m running an hour behind schedule.

Throughout the day, I also get calls from patients with urgent concerns. Although I have a few appointment slots blocked for last-minute appointments, often the only way to squeeze these patients in is to double book them. I try to only do this with truly urgent issues and sick kids, but I hate disappointing patients and telling them the next open visit is 2 months away. So that means sometimes, I end up with three patients, all scheduled for the same 20-minute slot.

What a mess.

Here are some of the reasons I run late:

A patient discloses suicidal thoughts.

A patient is elderly and speaks slowly.

A patient wants to talk about more than one medical problem.

A patient wants to talk about only one medical problem, but it’s a really complicated one that may not be straightforward.

A patient is experiencing housing insecurity, intimate partner violence, or addiction.

A patient recently lost a loved one and is grieving, and starts crying during the visit.

A patient really meant to tell me at the beginning, but has a really weird rash on their toe, and could they just show it to me and see what I think?

The electronic medical record went offline. (Rare, but humbling how much we depend on it when it happens!)

A patient wants to talk about erectile dysfunction but felt ashamed about it, so he waited until the visit was over, and I had one hand on the door handle and one foot out the door before he brought it up. (This is a typical “door handle complaint,” as we call it in the biz.)

A patient was just hospitalized, has 20 pages of discharge paperwork with her, but isn’t totally sure what happened, what it means for her going forward, and is depending on me to explain.

A parent doesn’t have childcare, so she brings her children with her to an appointment for the adult, and the kids are bouncing off the walls and have to be accompanied to the bathroom and are grabbing the keyboard while I type.

A patient is actually quite sick and needs to be seen in the emergency department, but came to the primary care clinic hoping that it could be treated here. (Which I absolutely understand — everyone likes to avoid the ER if they can!) We have to call EMS and transport the patient via ambulance to the hospital.

And I could go on, and on, and on.

Twenty minutes is not the right amount of time for anyone.

My sense is that most patients have no idea an appointment is only 20 minutes long. (Really 15, if you factor in the patient having their vital signs taken, the medical assistant reviewing their medications, and computer documentation.)

Or maybe people intellectually realize the visits are quite brief — there’s no shortage of doctors complaining about it online — but they don’t truly sense how quickly 20 minutes pass by.

Like most doctors employed by big hospital systems, I have very little control over my schedule. Patients are scheduled by a large, centralized call center (unless I give the go-ahead to double-book someone for a particulate date and time). I don’t have the discretion to schedule a patient for 25 or 30 minutes instead of the 20 minute template. And believe it or not, new patients get 20 minutes right alongside people I’ve cared for for years.

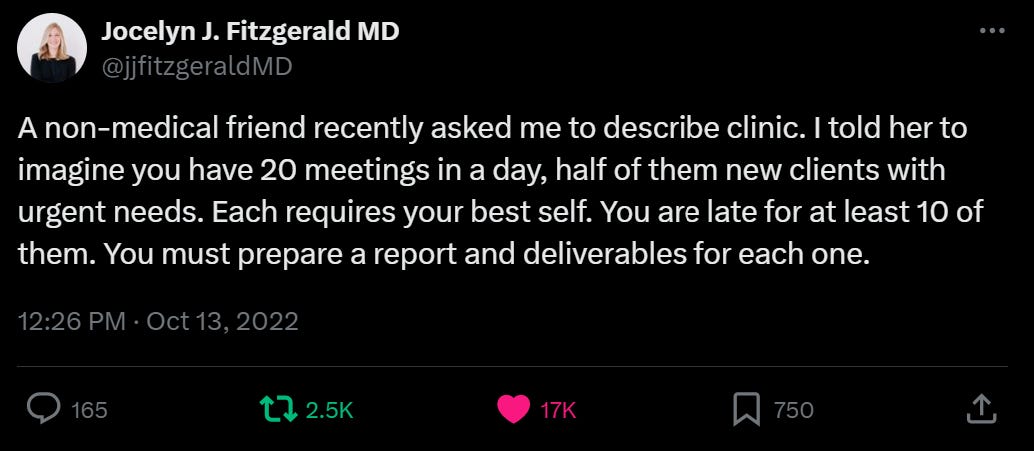

I loved this #MedTwitter quip from Jocelyn Fitzgerald, a gynecologist in Pittsburgh, describing the insanity of clinic:

I’ll also note that some patients don’t actually need a full 20 minute appointment. A birth control pill refill? A quick blood pressure check? That can take 5 minutes. It could also be done asynchronously, which means the patient messages me about it — checks their blood pressure or takes a pregnancy test at home — and I respond at a later time.

But the whole primary care enterprise has 20 minute visits as its foundation. It’s what we get paid for by insurance companies — so it’s what big, corporate health systems emphasize. We don’t get paid extra if we take 40 minutes with a patient, and we don’t get paid at all if we respond to a patient email.

Since insurance companies will only reimburse doctors for these short, synchronous visits, that’s our unit of engagement in primary care. I don’t have room in my day for anything else. Our bosses say, “Twenty minutes it is.” It goes without saying that this inflexibility isn’t great for patients.

(As an aside: There’s been enormous progress with telehealth since the pandemic, which I firmly believe is an important tool for effective primary care. It allows me to schedule phone calls or video chats with my patients, so we don’t play phone tag or leave voicemails with sensitive info. And people don’t have to come in for an in-person visit, something my busy patients really appreciate.

Most insurance companies will reimburse at a higher rate if we do a video chat rather than a phone call. This is often a struggle for my patients, since many don’t understand how to use the technology, or their connection isn’t strong enough for a smooth video visit.

Interestingly, I think telehealth can flip the power dynamic between doctors and patients on its head. I’ve written about this before for McSweeney’s and NPR.)

So this is why I’m always late. The system is not designed for deep listening or meaningful conversations. It’s designed to shuffle patients in and out, as quickly as possible.

If I push back against it at all — by not ushering out a sobbing patient, or asking a follow up question when an elderly patient mentions offhand that she feels dizzy — I end up behind schedule, apologizing all day for running late.

It makes me think of this classic essay by the physician writer Danielle Ofri in the New York Times (gift link).

It is true that health care has become corporatized to an almost unrecognizable degree. But it is also true that most clinicians remain committed to the ethics that brought them into the field in the first place. This makes the hospital an inspiring place to work.

Increasingly, though, I’ve come to the uncomfortable realization that this ethic that I hold so dear is being cynically manipulated. By now, corporate medicine has milked just about all the “efficiency” it can out of the system. With mergers and streamlining, it has pushed the productivity numbers about as far as they can go. But one resource that seems endless — and free — is the professional ethic of medical staff members.

This ethic holds the entire enterprise together. If doctors and nurses clocked out when their paid hours were finished, the effect on patients would be calamitous. Doctors and nurses know this, which is why they don’t shirk. The system knows it, too, and takes advantage.

Clinic is chaos. That’s part of what I love about it. I love being able to be nimble, to help my patients with everything from depression to a toddler's ear infection to diabetes to gender affirming care.

But I need time to be nimble, to meet my patients’ needs safely and effectively. Twenty minutes isn’t the right amount of time for me, and it isn’t the right amount of time for them.

P.S.: Are you registered to vote? I love this organization and just ordered a free badge to wear at work. I’m trying to talk to all of my patients about voting this fall. Let’s do this.

All of this!! I have thought about writing something like this to explain to my patients, though I agree that most patients who have been in the system for a while get it, for better or worse! It's new or young patients who may be confused, not knowing everything else we are juggling. I was heartened by a patient Press Ganey comment that said "I answered the question about wait time indicating that I waited more than 15 minutes beyond my appointment time. Personally, the wait time is not a problem for me since I know I will have [the doctor]'s full attention when we are together in the exam room and, I assume, the reason I am waiting is that she does this for all of her patients." When my day is running extra behind, I try to remember this! (It does still annoy me a bit that this question exists because it implies that being seen within 15 minutes is the expectation, when if we are trying to do things that we know are good for health outcomes like fitting complex patients in to provide continuity of care, it generally does mean we'll end up running late.)

I am lucky to have 30 minute visits right now, instituted thanks to the pandemic but retained now since my clinic has been able to demonstrate sufficient RVUs to merit it, with a usual practice of some double booking and doing dual preventive + E&M visits where appropriate. The new coding scheme of being able to bill a 99215 for 40+ minutes spent on the day of service has helped, since a lot of my visits wouldn't have met high complexity criteria for medical decision making but require a ton of time in care coordination or counseling/motivational interviewing. However, if I was on a 20 minute template I probably wouldn't code many 99215s for time since spending that amount of time would mean I'd have no hope of being able to eat lunch. I like that it allows me more time to get to know my patients and talk about overall health goals, but it creates some access challenges which I haven't totally decided how to manage since my panel size is still better fit to the 20 minute standard. It means many of my patients go to urgent care/virtual care for the quick visits (UTI, URI, vaginal discharge, STI check) and only see me for higher complexity issues or for an "annual physical" where they update me on everything that has occurred the last year and a few other things they've been saving for me as their PCP, which can be a lot!

What a perfect list! I try not to feel bad about being late anymore, since as you point out it’s clearly not our fault. I think my patients don’t usually mind because they know it evens out in the end since I will always go through their entire Notes app list of questions and answer their questions about siblings I am not seeing 😊 I love the issues you choose to write about and bring visibility to, keep up the great work!